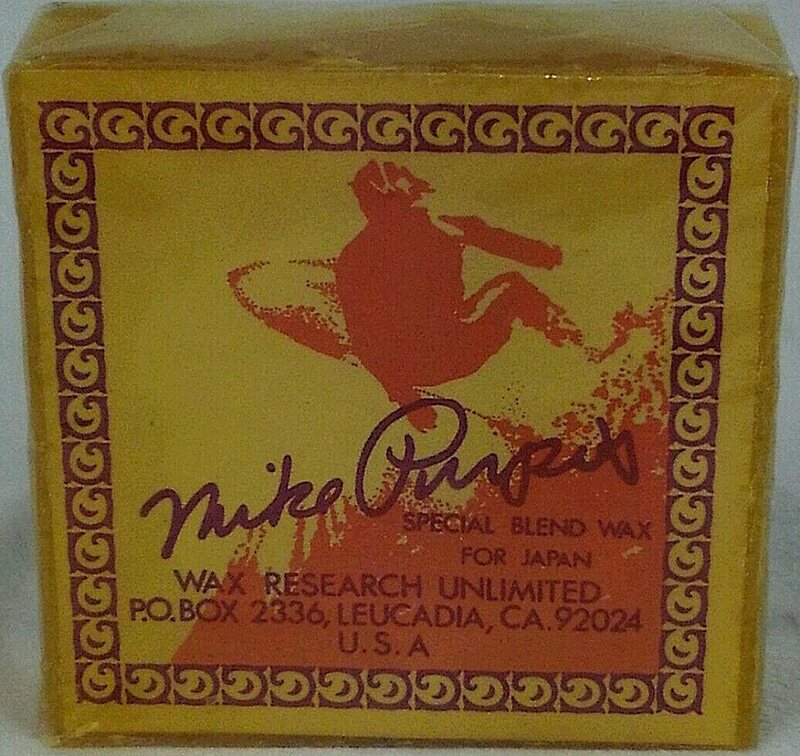

"Second Chance" South Bay Golden State's true story about Mike Purpus and Dr Todd Shrader.

A decade ago, Mike Purpus gave up on surfing. The former surf champion—widely considered the only California surfer who was competing regularly and successfully in the pro circuit during the early and mid-‘70s—didn’t drop his passion because he’d lost interest. He dropped it because he couldn’t walk anymore. “I was going through 15 aspirin a day and five Advil a night,” says the South Bay local. Purpus, then 65, was suffering from extreme arthritis in his hips during the early 2000s. His mobility was so severely limited, it took him nearly 15 minutes to hobble in pain out of his Redondo Beach apartment and walk across the street. “His hips were almost what we call ‘ankylosed,’ which means it was pretty much fused,” says Dr. Todd A. Shrader of the Torrance Orthopaedic & Sports Medicine Group. “There was absolutely zero movement in his hips.”

During the height of his surfing career between 1967 and 1976, Mike was one of the best surfers in the world. He competed in surfing contests across the globe, including the United States Surfing Championships, the Peru International and the Makaha International.

“My dad couldn’t keep me out of the ocean, so he just said, ‘I give up. I’ll get him a surfboard.’”He was also a five-time invitee to the Duke Kahanamoku Invitational Surfing Championship on the North Shore of Oahu, which during the 1970s was considered the sport’s premier competitive event. Astute locals will also notice his name on the Hermosa Beach Surfer’s Walk of Fame on the Hermosa Beach Pier.

But by the 1980s, Mike found his surfing career and health waning. By the early 2000s, he was overweight, could barely walk and hadn’t surfed in years. Mike’s physician told him that if he ever wanted to walk without feeling blistering, burning pain, he’d need both of his hips replaced.

Financial obstacles made surgery difficult to pursue. Mike didn’t have health insurance, and his income—derived from a mix of bartending, judging local high school surf contests and writing a surf column for the Easy Reader—wasn’t exactly thriving either.

But Mike is a living, breathing reminder of the South Bay’s surfing pedigree, and fortunately for him, surfers here have a knack for taking care of local legends who helped put SoCal surfing on the map.

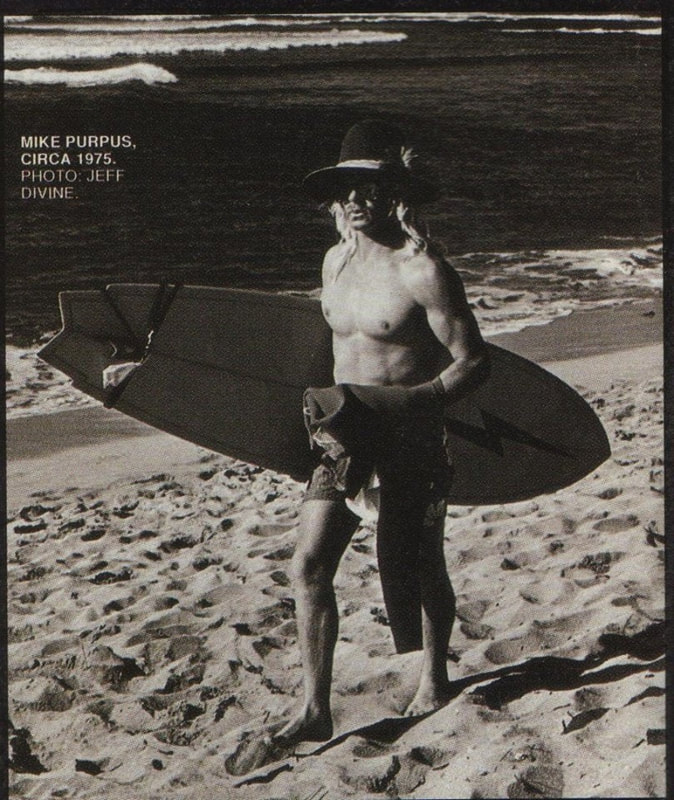

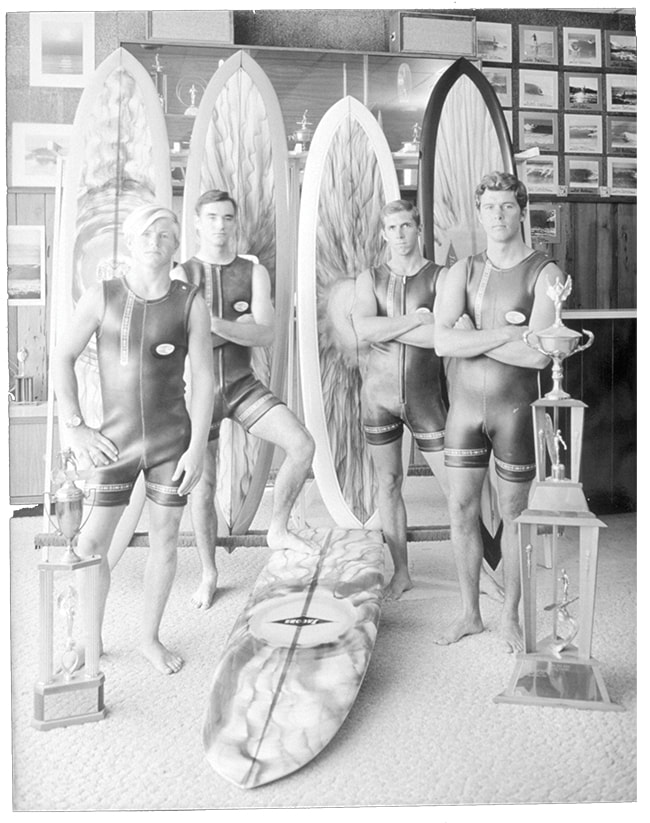

A Surfer Who Knows How to Laugh “From ’70 to ’75, I was the #1-rated surfer in the United States,” says Mike with a smile, which is something the man does quite a bit. Originally born in Santa Monica in 1948, his family moved almost immediately to Hermosa Beach, and he’s spent the rest of his life here in the South Bay. In 1958, he started surfing. At 16, the lean, blond beach rat was leaving Mira Costa High three hours early so he could surf—the school considered it training for his future career.

Fast-forward a few years, and Mike was quickly establishing himself as one of the most talented surfers in the Los Angeles area. During the 1965 U.S. Championships, he placed fourth. He moved up to the men’s division in 1967 and placed sixth.

He continued competing in the championships until the mid-‘70s. He ranked third in 1969 and 1970, and he won both the longboard and kneeboard divisions in ’75. In 1970, he won the Peru International, placed second at the 1971 Makaha International and competed in the World Surfing Championships in 1968, 1970 and 1972.

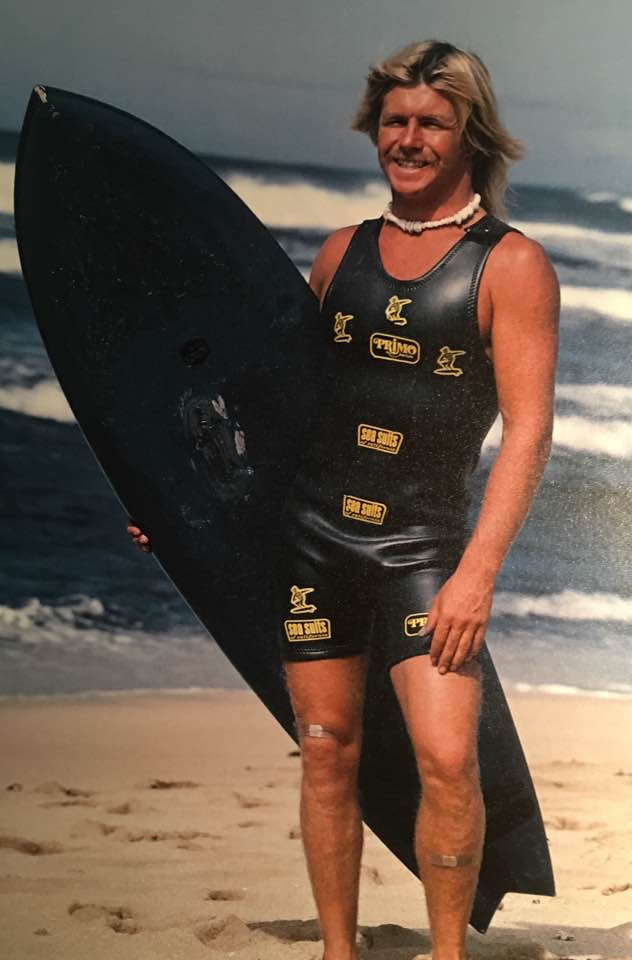

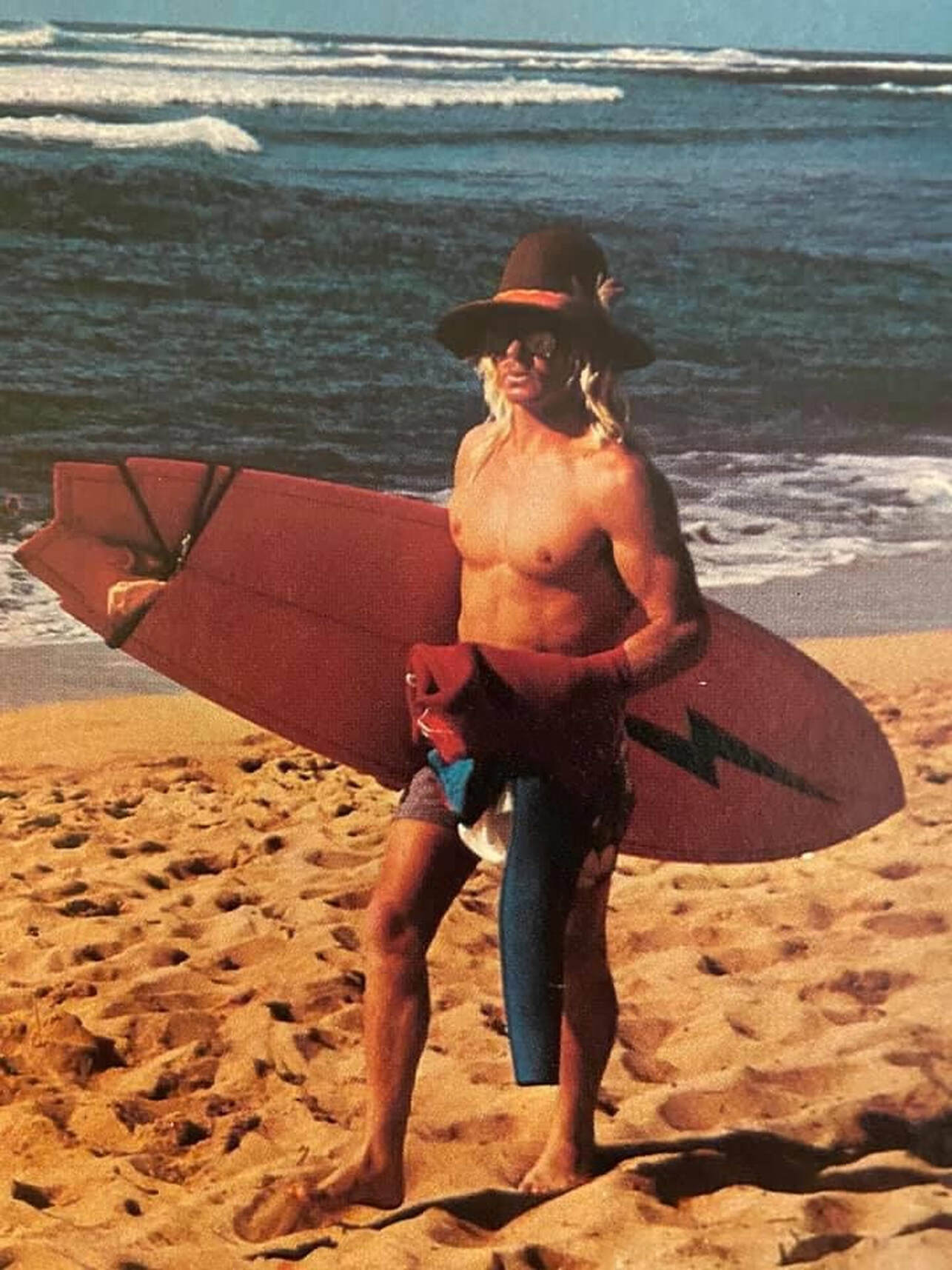

Mike’s surfing at the time can be described as raw and purely energetic. He’s in his element amongst the waves, and what he lacked in technical finesse, he made up for in sheer enthusiasm and dedication. According to Matt Warshaw’s The Encyclopedia of Surfing, during the ‘70s Mike taught himself how to switch up his stance, and he also developed a unique 270º cutback. He mastered a slew of additional tricks, including frontside and backside sideslips and 360s that put him on the forefront of the radical shortboard revolution.

During the height of his surfing career between 1967 and 1976, Mike was one of the best surfers in the world. He competed in surfing contests across the globe, including the United States Surfing Championships, the Peru International and the Makaha International.

“My dad couldn’t keep me out of the ocean, so he just said, ‘I give up. I’ll get him a surfboard.’”He was also a five-time invitee to the Duke Kahanamoku Invitational Surfing Championship on the North Shore of Oahu, which during the 1970s was considered the sport’s premier competitive event. Astute locals will also notice his name on the Hermosa Beach Surfer’s Walk of Fame on the Hermosa Beach Pier.

But by the 1980s, Mike found his surfing career and health waning. By the early 2000s, he was overweight, could barely walk and hadn’t surfed in years. Mike’s physician told him that if he ever wanted to walk without feeling blistering, burning pain, he’d need both of his hips replaced.

Financial obstacles made surgery difficult to pursue. Mike didn’t have health insurance, and his income—derived from a mix of bartending, judging local high school surf contests and writing a surf column for the Easy Reader—wasn’t exactly thriving either.

But Mike is a living, breathing reminder of the South Bay’s surfing pedigree, and fortunately for him, surfers here have a knack for taking care of local legends who helped put SoCal surfing on the map.

A Surfer Who Knows How to Laugh “From ’70 to ’75, I was the #1-rated surfer in the United States,” says Mike with a smile, which is something the man does quite a bit. Originally born in Santa Monica in 1948, his family moved almost immediately to Hermosa Beach, and he’s spent the rest of his life here in the South Bay. In 1958, he started surfing. At 16, the lean, blond beach rat was leaving Mira Costa High three hours early so he could surf—the school considered it training for his future career.

Fast-forward a few years, and Mike was quickly establishing himself as one of the most talented surfers in the Los Angeles area. During the 1965 U.S. Championships, he placed fourth. He moved up to the men’s division in 1967 and placed sixth.

He continued competing in the championships until the mid-‘70s. He ranked third in 1969 and 1970, and he won both the longboard and kneeboard divisions in ’75. In 1970, he won the Peru International, placed second at the 1971 Makaha International and competed in the World Surfing Championships in 1968, 1970 and 1972.

Mike’s surfing at the time can be described as raw and purely energetic. He’s in his element amongst the waves, and what he lacked in technical finesse, he made up for in sheer enthusiasm and dedication. According to Matt Warshaw’s The Encyclopedia of Surfing, during the ‘70s Mike taught himself how to switch up his stance, and he also developed a unique 270º cutback. He mastered a slew of additional tricks, including frontside and backside sideslips and 360s that put him on the forefront of the radical shortboard revolution.

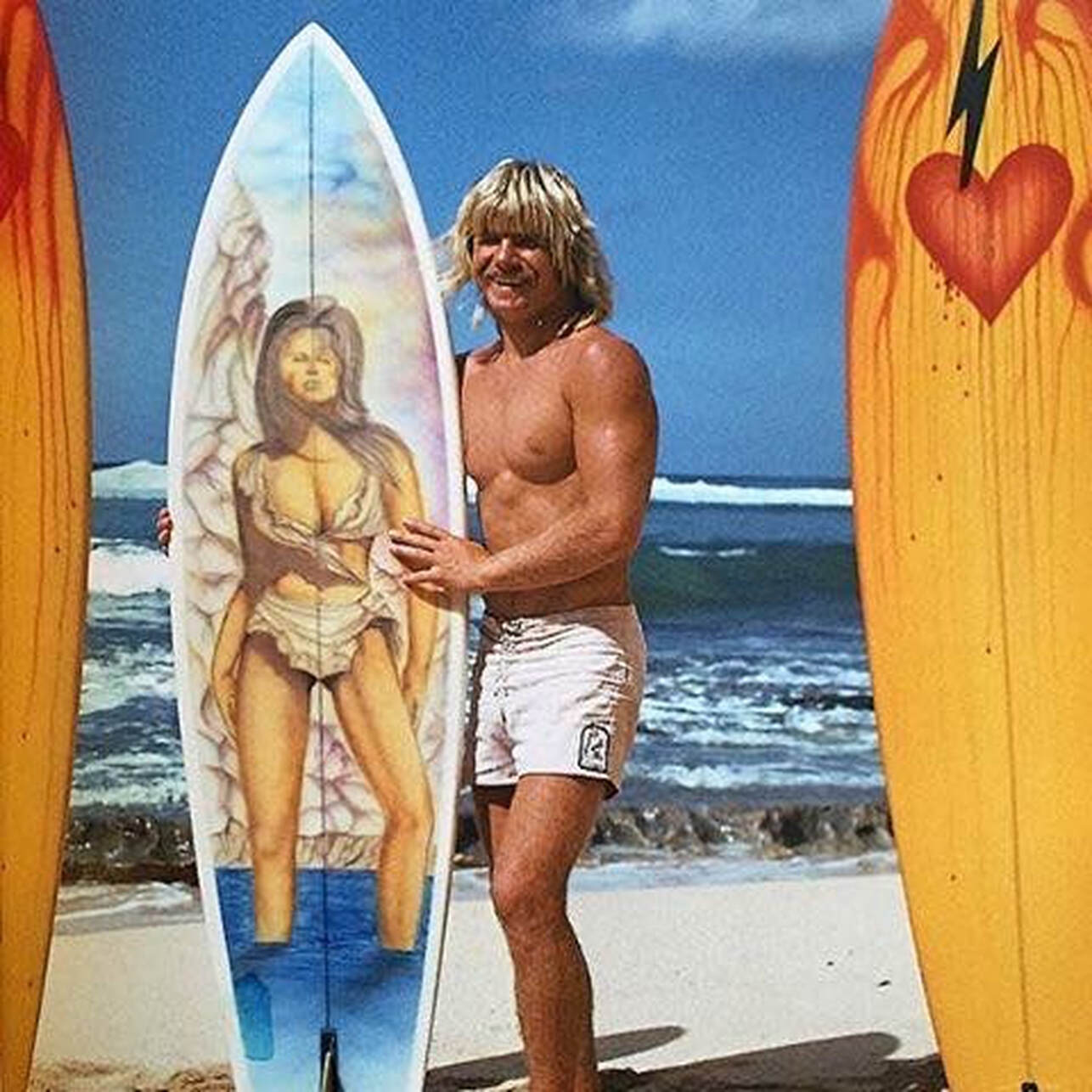

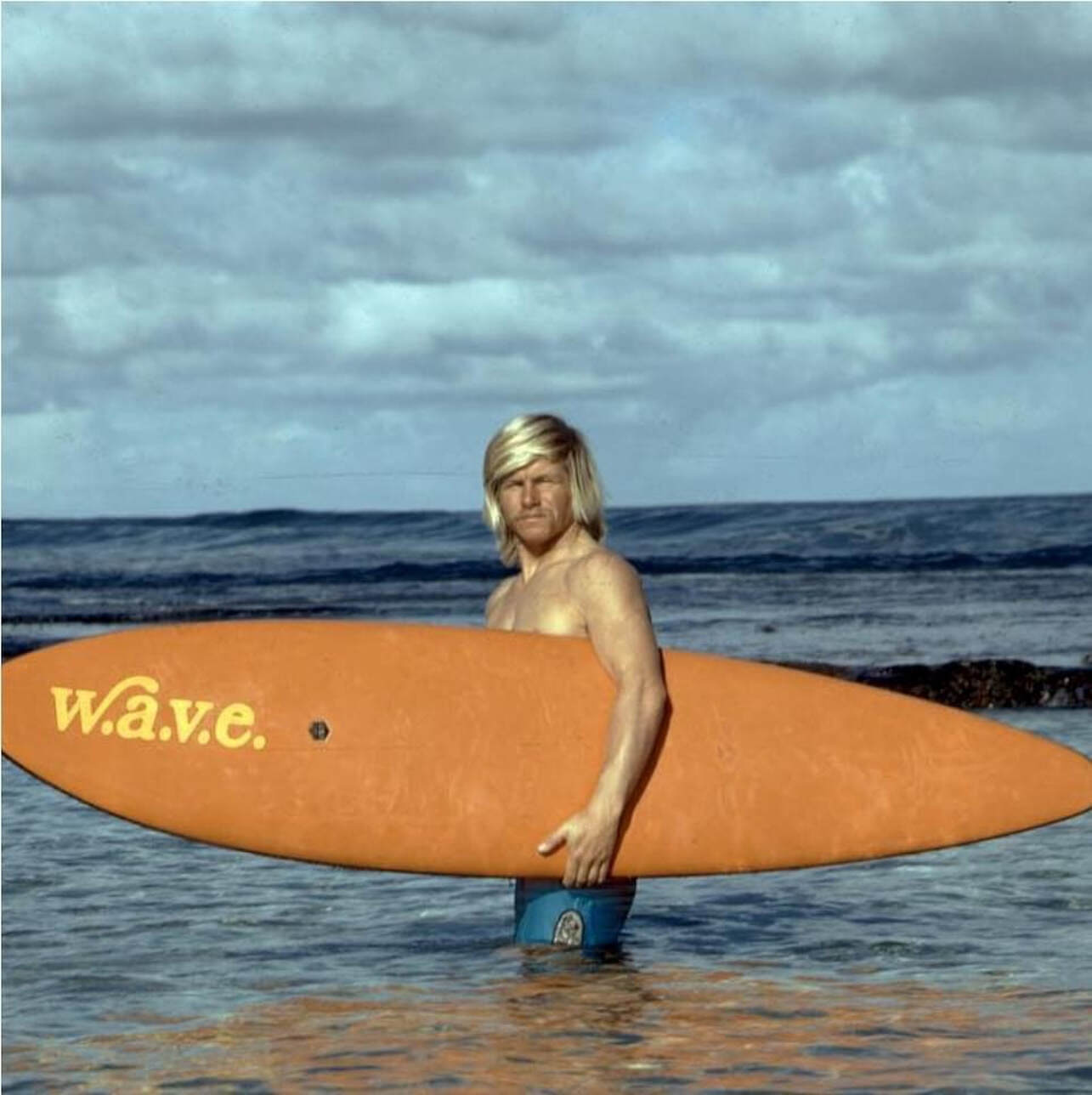

In his youth, Mike was the prototypical California surfer. Though he’s short, his frame was defined by powerful muscle. His shaggy, blond hair and mustache (coupled with an ever-present puka shell necklace and floppy, broad-brimmed leather hat) gave him a 1970s beach king look that seemed ripped from the cover of a Nixon-era Playgirl magazine. (Interestingly enough, Mike did actually pose in all his smiling, naked glory for the magazine in 1974, and asking him about it spurs a proud but mischievous smirk.) “I don’t even have a driver’s license,” Mike informs me with a laugh. “It expired in 1980 when I was in Australia for the pro circuit. I never got it renewed.” Mike’s affable nature defines him almost as much as his surfing does. He’s always on the verge of laughter and consistently searching for fun to be had.

In 1968, he made his first of three appearances on ABC’s The Dating Game (he eventually won a trip to Scotland). He also achieved some notoriety in a number of surf publications for having an image of Raquel Welch in her iconic fur bikini from One Million Years B.C. spray-painted on a surfboard. He then topped that by having another provocative image painted onto an additional board: This one depicted his blond, tan, teenage girlfriend at the time, nicknamed “No-Pants Nance,” holding a copy of Surfer magazine by her side and nothing else. The first time he brought the board out into the public here in the South Bay, Mike says that a mail carrier driving by took her eyes off the road to stare at him as he walked along. “She crashed straight into a fire hydrant,” he adds.

In his apartment now, the ceiling is covered with surfboards of all sizes (including his personal Hap Jacobs “Mike Purpus model” longboard, which the shop still sells). But “Nance” has her own special place right over the kitchen counter, which is jam-packed with decades worth of dusty surf trophies.

In 1968, he made his first of three appearances on ABC’s The Dating Game (he eventually won a trip to Scotland). He also achieved some notoriety in a number of surf publications for having an image of Raquel Welch in her iconic fur bikini from One Million Years B.C. spray-painted on a surfboard. He then topped that by having another provocative image painted onto an additional board: This one depicted his blond, tan, teenage girlfriend at the time, nicknamed “No-Pants Nance,” holding a copy of Surfer magazine by her side and nothing else. The first time he brought the board out into the public here in the South Bay, Mike says that a mail carrier driving by took her eyes off the road to stare at him as he walked along. “She crashed straight into a fire hydrant,” he adds.

In his apartment now, the ceiling is covered with surfboards of all sizes (including his personal Hap Jacobs “Mike Purpus model” longboard, which the shop still sells). But “Nance” has her own special place right over the kitchen counter, which is jam-packed with decades worth of dusty surf trophies.

In the early 1980s, a 30-something Mike found that his surfing career was starting to wane. He couldn’t support himself solely on surfing anymore, and he started bartending. By the time he was 50, Mike was no longer the muscled surf champ. He was overweight. His blond hair was chopped short and totally grey. And he was noticing that he was constantly fighting for breath, and walking—for whatever reason—was becoming surprisingly difficult. "It felt like I had a leprechaun hanging on my hip,” he says, “just jabbing me with an ice pick in my sockets.” He started popping Advil and aspirin like candy, but even with the pain medication and a decent bicycle, Mike couldn’t get around very well. He supplemented his bartending and writing income by judging high school surf contests, but even getting down to nearby Torrance Beach from his apartment for an early morning contest was proving arduous.

It would take him a half-hour minimum just to walk down the hill. Mike, at that point, was starting to understand that if he didn’t change his health quickly, he might not be able to surf—or even walk—ever again.

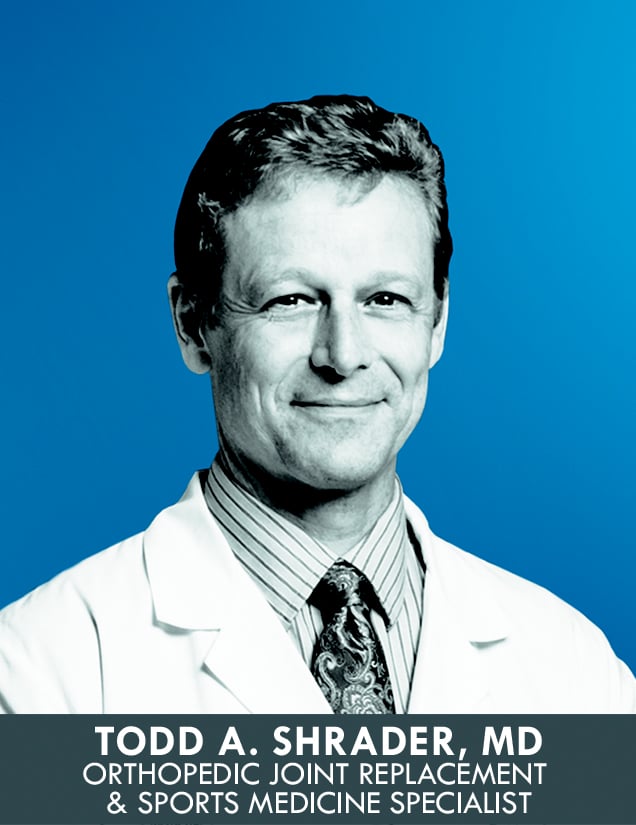

He’s a Good Guy in a Bad Way “My nickname in school was ‘Doogie How-ser,’” says orthopedic surgeon Dr. Todd Shrader. “When I was an intern, one of the staff members nicknamed me that—and it stuck like glue.” Dr. Shrader, 51, has a youthful appearance, which fooled Mike when the two first met. “I thought the guy was some sort of orderly. He looked like my waiter at the Chart House.” Dr. Shrader has spent most of his life here in the South Bay. His father, Richard, was also an orthopedic specialist. The Palos Verdes local surfs too, though with his schedule he often can’t find much time to get out into the water. Back in 2006, Mike was advised by the residents at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center to get in touch with Dr. Shrader after deciding his critically damaged hips needed to be examined in detail by an expert. “I didn’t really know who Mike Purpus was,” says the doctor. “I pulled up to my office, and I saw this guy walking across the street. And he walked like a penguin. He couldn’t move his hips. ‘Wow, that guy’s a mess’—that was my first thought. But who’s my first patient for the day? The guy walking across the street like a penguin.” When the two first met, Mike was in a painfully transitional phase. Earlier, he’d vowed to lose the weight he’d put on, and every day he walked up and down the hundred steps that led from his home near Knob Hill Avenue down to the beach. He’d lost most of the excess weight, but the pain in his hips was still tremendous. “I’m not exaggerating: It was one of the worst-looking hips I’ve ever seen,” says Dr. Shrader. Aside from their “ankylosed” nature, there were bone spurs that nearly enclosed his hips. A complete hip replacement was Mike’s only option. But Mike didn’t have health insurance, and the surgery—without adding in hospital charges and other fees—would cost approximately $5,000. After talking, and after Mike gave Dr. Shrader a rundown of his surfing career, the two made an arrangement. In return for Dr. Shrader’s services, Body Glove offered to provide him with a wetsuit for one hip replacement, and Bing Surfboards offered him a board for the other.

It would take him a half-hour minimum just to walk down the hill. Mike, at that point, was starting to understand that if he didn’t change his health quickly, he might not be able to surf—or even walk—ever again.

He’s a Good Guy in a Bad Way “My nickname in school was ‘Doogie How-ser,’” says orthopedic surgeon Dr. Todd Shrader. “When I was an intern, one of the staff members nicknamed me that—and it stuck like glue.” Dr. Shrader, 51, has a youthful appearance, which fooled Mike when the two first met. “I thought the guy was some sort of orderly. He looked like my waiter at the Chart House.” Dr. Shrader has spent most of his life here in the South Bay. His father, Richard, was also an orthopedic specialist. The Palos Verdes local surfs too, though with his schedule he often can’t find much time to get out into the water. Back in 2006, Mike was advised by the residents at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center to get in touch with Dr. Shrader after deciding his critically damaged hips needed to be examined in detail by an expert. “I didn’t really know who Mike Purpus was,” says the doctor. “I pulled up to my office, and I saw this guy walking across the street. And he walked like a penguin. He couldn’t move his hips. ‘Wow, that guy’s a mess’—that was my first thought. But who’s my first patient for the day? The guy walking across the street like a penguin.” When the two first met, Mike was in a painfully transitional phase. Earlier, he’d vowed to lose the weight he’d put on, and every day he walked up and down the hundred steps that led from his home near Knob Hill Avenue down to the beach. He’d lost most of the excess weight, but the pain in his hips was still tremendous. “I’m not exaggerating: It was one of the worst-looking hips I’ve ever seen,” says Dr. Shrader. Aside from their “ankylosed” nature, there were bone spurs that nearly enclosed his hips. A complete hip replacement was Mike’s only option. But Mike didn’t have health insurance, and the surgery—without adding in hospital charges and other fees—would cost approximately $5,000. After talking, and after Mike gave Dr. Shrader a rundown of his surfing career, the two made an arrangement. In return for Dr. Shrader’s services, Body Glove offered to provide him with a wetsuit for one hip replacement, and Bing Surfboards offered him a board for the other.

With the assistance of his now-retired father, Dr. Shrader performed an anterior hip replacement (a new and time-intensive type of hip replacement surgery that’s ideal for an active-lifestyle patient) on one hip first. This type of surgery usually takes two hours—but this one took close to four. Mike returned a year later to have the other “good” hip fixed. He informs me that the surgery was supposed to be a piece of cake—but the doctors found a sizeable bone spur that took hours to remove. It was so large and grisly-looking when Shrader showed the growth to Mike after surgery, it started haunting him in his sleep. “I kept having these nightmares while I was in the hospital recovering,” says Mike, shaking his head, “that the bone spur got up and unscrewed the lid of the jar it was in, and it left a trail of dead candy stripers. And I’d wake up in a cold sweat with the spur trying to gnaw its way back into my hip.” When asked for details on why he helped Mike, Dr. Shrader speaks plainly about his charitable act. “I just felt I was helping someone out who needed it. I did it for who he was.”

Back to the Waves, “Well, I haven’t had an aspirin since,” says Mike. It’s been six years since his last hip surgery, and the former surf champion is spending as much time as he can back in the water. He’d been hesitant at first, especially since it had been years since he’d last surfed, and he mentions that he had to relearn how to surf all over again. But Mike quickly picked surfing back up, and he now competes regularly in South Bay Boardriders Club contests. During the Spyder Surf Series “King of the South Bay” contest, Mike finished in third place overall for the longboard division. Mike says he’s in the water every day now, even if the waves are a no-show. “You know why? Because of Todd,” he says. “I feel like I let Todd down if I don’t surf.”

Thanks to an act of charity from a fellow surfer—as well as local surf companies, including Bing Surfboards, Hap Jacobs Surfboards and Body Glove—a South Bay legend was able to return to his one, true passion. And Mike wouldn’t have it any other way.

“My whole life is a highlight reel,” says Mike about the defining moment of his surf career. He switches the conversation to the North Shore and the monster waves he surfed there as a teen. Mike, as always, is happiest when he’s spreading the good word about the sport he loves.

Back to the Waves, “Well, I haven’t had an aspirin since,” says Mike. It’s been six years since his last hip surgery, and the former surf champion is spending as much time as he can back in the water. He’d been hesitant at first, especially since it had been years since he’d last surfed, and he mentions that he had to relearn how to surf all over again. But Mike quickly picked surfing back up, and he now competes regularly in South Bay Boardriders Club contests. During the Spyder Surf Series “King of the South Bay” contest, Mike finished in third place overall for the longboard division. Mike says he’s in the water every day now, even if the waves are a no-show. “You know why? Because of Todd,” he says. “I feel like I let Todd down if I don’t surf.”

Thanks to an act of charity from a fellow surfer—as well as local surf companies, including Bing Surfboards, Hap Jacobs Surfboards and Body Glove—a South Bay legend was able to return to his one, true passion. And Mike wouldn’t have it any other way.

“My whole life is a highlight reel,” says Mike about the defining moment of his surf career. He switches the conversation to the North Shore and the monster waves he surfed there as a teen. Mike, as always, is happiest when he’s spreading the good word about the sport he loves.

*The above is a reprint of a wonderful article done featuring Mike & Dr Shrader from the South Bay Golden State magazine about half 6 years ago.

Mike Purpus Videos

Great interview of Mike Purpus

Check out "Mr 360" doing his thing in the '70's

Mike Purpus Encyclodedia of Surfing

The Legendary Rick James Thumb Story

Great interview of Mike Purpus

Check out "Mr 360" doing his thing in the '70's

Mike Purpus Encyclodedia of Surfing

The Legendary Rick James Thumb Story